|

|

The Riverbend Down Syndrome Association is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization and can receive tax deductible contributions. Our Employer Identification Number is: 14-1982424.

Mark your calendars; please attend our next parent support meeting: Meet and Greet, January 25th 6:30 p.m. at LeClaire Christian Church, 1914 Esic Drive, Edwardsville, IL 62025. Contact: Sara and Tammy, E-mail: support@riverbendds.org

Another View of Sheltered Workshops by Debbie Cole is a commentary on Sue Brown's A Tired Old Cliché Revisited, printed in August 2008.

The on-line version of the Fiftieth anniversary of trisomy 21 will be in the original French due to copyright restrictions.

From the author of A Different Kind of Perfect: the book is about the realization that perfect comes in all shapes and sizes... [and] the greatest message that came out of our experience is to see that life is not about perfection but love; and if you love, your choice is perfect because it's our capacity to love and not other's standards that determine what's perfect.

Local Events

The fifth annual Puttin' for Down Syndrome golf tournament and clinic was held at Clinton Hills Golf Course in Swansea, IL, on Friday, Sept. 25. The charity golf event and silent auction featured 22 golf teams, and early estimates showed that about a total of $8,000 was raised, which will be split between Down Syndrome Center at St. Louis Children's Hospital, and the DSAGSL.

|

| Back row: Emmanuel Bishop, Tim & Alex Nienhaus, golf pro Dan Polites. Middle row: Ryan Creasy, Jamie Lee. Front: Willie Love III. |

|

|

Down Syndrome Articles

Pujols helps launch Down syndrome center in Chesterfield by Greg Jonsson. Nov. 11, 2009. Reprint permission granted by Mark Learman, E-mail: MLearman@post-dispatch.com. © 2009 St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

CHESTERFIELD — Kids in the area with Down syndrome generally have access to good medical care. Then they turn 18 and their options dwindle.

That's what Beth Schroeder, former president of the Down Syndrome Association of Greater St. Louis, found when she talked to parents, and the challenge she saw facing her with her own son. He was getting too old for his pediatrician, who was well-versed in Down syndrome's challenges, but it wasn't easy finding a doctor ready to handle the challenges as he became an adult.

"There are medical issues and other issues involved," Schroeder said. "It's hard to just find a doctor in the Yellow Pages who's going to understand all that."

|

| Cardinals first baseman Albert Pujols is greeted by Ethan Schroeder (left), of Eureka,, and Isabel Hogan (center) of St. Louis during an opening reception Wednesday evening for the Albert Pujols Wellness Center for Adults with Down Syndrome at St. Luke's Desloge Outpatient Center in Chesterfield. (Photo by Whitney Curtis/P-D) |

|

|

|

Schroeder and others brought their concerns to St. Luke's Hospital last year, and Wednesday night attended the opening of the Albert Pujols Wellness Center for Adults with Down Syndrome at the hospital.

With the support of Pujols, who designated a $70,000 award from the Major League Baseball Players Trust to the center, and others, the center began taking patients last week.

"It's a special day not just for the Pujols family but for all families with adults with Down Syndrome," Pujols said at the opening ceremony.

Pujols and his wife, Deidre Pujols, have a daughter with Down syndrome and have supported a number of related causes in the area. Albert Pujols said he wants those sorts of things to be his legacy.

"It's not what I do on the field, it's what I do off the field," the Cardinals first baseman said. "I want people to remember me for that."

Representatives at St. Luke's say the center will fill a void in the community and hope it can grow and become a model for other cities.

Angela Jackson brought her brother James Judy to check out the offerings. Judy, 41, has Down syndrome and lives in a group home in Alton. Jackson said Chesterfield would be a long trip on a regular basis. But she said the services are needed and she wanted to see the center and think about what it could offer for her brother. For his part, Judy was just excited to see Pujols.

"People with Down syndrome have very specific needs," Jackson said. "It's difficult to find physicians that have experience with people with those needs. We wanted to see what resources they offer here."

Schroeder said she hopes the center fits the bill.

"Parents of people with Down syndrome want the same as any other parent," Schroeder said. "We want our children to be happy, healthy and successful. You just need a few more people helping them, and this is huge."

Another View of Sheltered Workshops by Debbie Cole. E-mail: purplemonkey003@yahoo.com. Family Connection, Spring 2009, Vol. V, Issue II, p. 7. Reprint permission granted by Linda Orso and the author.

As an occupational therapist and a parent of a child with Down syndrome, I would like to share my thoughts about negative portrayals of sheltered workshops and day programs.

There are currently many adults with Down syndrome who are happily and productively employed at area sheltered workshops. These employees are working at a level commensurate with their intellectual abilities. They and their caregivers feel that they are being challenged appropriately.

Terms such as a "tag-along life" to describe people with disabilities who "do what their parents do" seem somewhat insensitive both to these adults and to their parents. To question if someone is a contributing member of society based on their involvement in a day program or a sheltered workshop may cause needless hurt feelings to the caregivers who have made these choices for individuals with disabilities and to the employees of these workshops. Area employers are under no obligation to hire people with special needs. If someone cannot find or hold a job in the community or in a sheltered workshop, isn't a day program with some structured activities preferable to sitting at home and watching TV?

As an occupational therapist and a parent, I know that all people, including people with Down syndrome, have varying levels of intellectual abilities. While some people with Down syndrome thrive in community-based employment there are others who, for many reasons, are simply not able to do so. In addition to intellectual functioning, there are other factors that may determine if someone with Down syndrome can perform well in community-based employment. Tolerance for changes in routine, speech intelligibility, attention to task, and reaction to noise levels are some of the factors that can affect the employment options available to someone with Down syndrome.

I believe that it is imperative that parents of people with Down syndrome stop looking down at sheltered workshops. A common myth assumes that employees of sheltered workshops have no socialization opportunities or do not have "the dignity of being a contributing member of society". This is simply untrue. It is also offensive. As an occupational therapist, I would hope that none of my colleagues are so misguided that they would view employment in the community as the only "good" choice for people with Down syndrome. Shouldn't they have options in employment like anyone else?

My oldest daughter is currently a sophomore at Harvard University. I am extremely proud of her, but I do not look down upon students who are enrolled at state universities or technical schools. People would be appalled if I questioned why someone chose to attend a state college, if I wondered if they were being adequately challenged at a technical school. I would be considered rude, and rightfully so, to imply that someone who chooses a different academic or career path is somehow not a contributing member of society.

The truth is that every graduating senior is different. For some, Harvard University is a perfect fit. Others thrive in a less academically intense environment. And still others will succeed in a learning environment that stresses hands-on job training.

All of these individuals have different talents, different levels of abilities and have chosen a learning environment that suits them. No doubt they will choose careers that suit their own unique set of talents and abilities. Some of their jobs will be demanding and high-stress. Others will be less so. Some will pay more than others. Some will require high levels of academic preparation and others will require years of apprenticeship. Some will require a strong focus in a particular science; others will require an incredible amount of craftsmanship, patience and hard physical labor. All of these occupations are honorable and dignified. Persons employed in these endeavors deserve our respect, never our derision.

And so it is with people with Down syndrome. Some will thrive in a community-based employment situation. Others will be happier in a more structured environment such as a sheltered workshop. And yes, some will not be able to handle the particular challenges that either a community-based employment or a sheltered workshop entails. Perhaps they have other issues that preclude their functioning in either of the above situations. A day program may fit their particular needs extremely well. And no one should look down upon them. Whatever career paths people with Down syndrome choose, they deserve our respect, never our derision. I will cherish the day when ALL parents of people with Down syndrome support ALL choices available for people with Down syndrome.

A Different Kind of Perfect; The Story of Parents' Choices and A Special Child by George Michael Lane. Blog: http://adifferentkindofperfect.com. E-mail: yumaschin@aol.com. Gom Parclete Press (2008). Excerpts reprinted with the permission of the author.

Chapter 1, p. 15-20: "God's little clowns"

Although Mark Twain said that no one ever got lost on a straight road, our lives also include many roads that bend and turn-roads on which we can find ourselves lost, alone, and without reason or compass.

I called Thea. "Honey, what's new?"

Before she could answer, I mentioned that it had been three weeks since her amniocentesis. However, Thea didn't comment. At three weeks, I felt a little less anxious about the results. Nevertheless, Thea didn't seem to share my feeling.

"Same old, same old... nothing new," she said.

"It's week three, right?"

"Yes, George." Thea sounded distant.

"Honey, is something wrong?" I asked. Again, she said nothing. Her silence intensified my anxiety; I was not sure that I wanted her to answer. Suddenly, she burst into tears.

"I didn't want to say anything," she cried. "Not when you're away. I just wanted to wait until you came home."

"What are you talking about?"

"The doctor phoned today."

"Your obstetrician?"

"Yes." She continued tearfully, "He said our baby has Down syndrome."

It was Tuesday, October 21, 1986, and I had been meeting with The Graham Companies' employees at the Wilmington plant in North Carolina. The Glass, Molders, Pottery, Plastics, and Allied Workers International Union had been trying to organize them. Working out of the corporate office in York, Pennsylvania, I joined Graham only a year ago after having left ITT. The union had petitioned the National Labor Relations Board for a representation election. I've always thought that if a company gets unionized, it deserves it. Unfortunately, we deserved it, and I was now frustrated. Thus, I needed to relax. I was staying alone at the Holiday Inn, and I planned to watch Game 3 of the World Series being played at Fenway between the Red Sox and the Mets. The Mets had lost the first two games at home, and the vision of the Red Sox world championship that had been denied to me since childhood was now becoming real. I ordered a pizza and beer delivery to my room. I decided to phone Thea, who was five months pregnant, before I settled in for the game. Although we hadn't planned the pregnancy, we definitely weren't cautious about preventing it. Mara, our youngest, was now going to school all day. Therefore, Thea was experiencing the empty nest syndrome. Lately, Thea had been thinking of finding a job. She has a bachelor's degree in nursing. However, she missed having a child at home, and often she talked about getting pregnant. We decided to leave it up to the Lord. "Que sera, sera," she had said hopefully. Therefore, it wasn't surprising when Thea informed me of the consequence of our love-a love that wasn't ordinary, but wonderful and passionate.

Thea was 41 and at greater risk with her pregnancy, because at that age, the odds of having a baby born with Down syndrome are 100 to 1. Since these odds made us anxious, Thea decided to have prenatal testing done at the Hershey Medical Center to determine if there were any genetic problems or abnormalities. Additionally, she had an amniocentesis and an ultrasound screening; both are routine diagnostic procedures recommended for pregnant women over the age of 35. The amniocentesis presented some risk of miscarriage. The amnio, as it is called, involved a neck, and he spent entire days standing extracting and analyzing fluid from Thea's amniotic sac, where the fetus resides. The ultrasound, which has no risk, uses very high frequency sound to produce an image of the fetus. The doctor prepared Thea's abdomen for the ultrasound by rubbing a clear gel on it that conducts the high frequency sound waves through the skin. As the sonogram wand glided across her abdomen, an image of our baby appeared on the monitor. The baby was delicate and tiny but discernible; its little feet were pressed against the wall of Thea's stomach. Everything appeared normal, and the doctor proudly produced a black and white Polaroid-type print for us. Gently, the doctor then inserted a needle through Thea's abdomen and extracted a small amount of fluid from the amniotic sac around the fetus. She didn't seem to have any discomfort. She looked content, even sexy. Her protruding stomach was stretched firm. In clothing, her condition was not obvious; however, her exposed stomach evinced nature at work. The doctor advised us that it would take about four weeks for the results of the amniocentesis. During this time, he would analyze the chromosomes in the fetal cells that the fluid contained. Normally, he identified genetic problems in a few weeks. Therefore, the closer we got to four weeks, the less likely that there would be any problems. The amnio would also tell us the sex of the baby.

I didn't know what to say to comfort Thea. We endured a momentary silence that seemed like an hour following her announcement about our baby. The words Down syndrome conjured up the most frightening images. I envisioned the young person that we had seen at Hershey's theme park the past summer, who appeared to be in his thirties, but it was difficult to tell. He was about 5'4", bald, and obese. He had slanted eyes, a short flattened skull, protruding lips, and a long tongue that hung from his mouth and seemingly lacked muscle control. Also, there was the person whom I remembered from my youth. His large head appeared to be set on a square body without a neck, and he spent entire days standing on a city sidewalk watching the passing traffic. Mongolian idiot," someone would often point and say.

"George, are you okay?" Thea asked.

"Yes, honey. I'll get the first flight to Harrisburg. I'm going to take the rest of the week off so we can talk."

"All right," Thea said.

"I love you. Everything is going to be all right," I said, trying to assure her and myself, despite Thea's obvious despair and my delayed response.

"I love you, too."

"See you soon," I said, hastily returning the receiver to its cradle.

In his book, The Clowns of God, Morris West called children with Down syndrome, described as mongols, "les petites bouffonnes du bon Dieu—God's little clowns." West writes:

People who are able to keep them in the family group find that it is like having a new baby in the house all the time.... But, of course, it is when the parents age and the child comes to adolescence and maturity that the tragedies begin. The boys may become very rough and violent. The girls are easy victims to sexual invasion. The future is dark for both parents and child.... It's sad.

I couldn't believe that this was happening to us; I was afraid and confused. In M.C. Escher's lithograph, Ascending and Descending, there is a never-ending stairway on which two lines of monks climb in different directions. One line climbs up ad infinitum; the other line descends endlessly. All are going nowhere. That's exactly where I felt we were. Damn! I thought. This isn't fair. This isn't the plan. We are going somewhere. We are on a journey that we have taken three times before.

Chapter 26, p. 198: Naked to the world

"The least amount of difference between a child with disabilities and a child without disabilities may be the day that they are born, naked to the world," says Lou Brown [Dr. Lou Brown, professor of education at the University of Wisconsin]. "But then, because of the way our society separates the child with disabilities into 'special services,' he or she becomes 'different.' "

Therefore, our schools simply reflect how society reacts to those who are different. Unfortunately, if we are too trusting, our children's best interests will not be served. On the other hand, we must place some trust that the goodness of people will prevail and move us to more integrated and inclusive school communities where the differences about us actually make a difference, and where the best and most talented among us grow up touching people with disabilities. Then, once again, we may all be naked to the world.

Chapter 26, p. 195: Naked to the world

My point is not to beat up the teachers and administrators of our high schools, but rather to communicate to parents the importance of being an advocate-and sometimes an "iron willed" advocate. If you're not advocating for yourself, no one else will do it for you. Follow your heart, and generally you'll do the right thing for your child even though at times you'll feel alone and doubting or second-guessing your decisions. Generally, regular classroom teachers aren't equipped to teach our children and often don't want to. It's up to us to fight for their inclusion and remain steadfast about our beliefs. "Remember that the vast majority of innovations that have taken place... happen because parents and their children become dissatisfied with 'what is,' says David Pitonyak [Dr. David Pitonyak, nationally recognized consultant to people with disabilities]... .

George Michael Lane is a former Senior Vice-President of Global Human Resources, earned his B.A. in Political Science from Rutgers College, New Brunswick, New Jersey, and is a certified Senior Professional in Human Resources (SPHR). He lives with his wife, Thea, and daughter, Amy, in Camp Hill, PA and on Great Diamond Island, Maine.

Dragen, Here is your letter by Lyn Burr Brignoli. America. Oct. 27, 2008. Reprint permission granted by Bro. Frank Turnbull, S.J. © 2009 America Press Inc. All Rights reserved.

Dragen was 6 years old when he first came to me for religious instruction. Our director of religious education had never accepted a child with Down syndrome into the parish program before, and she did not really know what to do with him. Yet she thought I seemed like a natural for the job.

I had met our director only a few months earlier. I had never taught religion before. I had only recently been received into the Catholic Church during the Easter Vigil at St. Mary's in 1998. Though I had no experience with Down syndrome myself, I was intrigued with the challenge: How do you talk about something as abstract as God with a child who has Down syndrome?

Dragen (pronounced DRAY-gun; his father is from Bosnia-Herzegovina) was small for his age, a bright, mischievous boy with a marvelous smile. He was already familiar with many prayers and the Mass. I eventually learned that from an early age he had been attending Mass most mornings with his grandmother. He would enter our little classroom, look at the crucifix on the wall, put his arms out to his side and drop his head down, imitating the posture of Jesus on the cross, a gesture that unnerved me at first.

In our first weeks and months together, I was for the most part poking around in the dark. Not having any teaching materials and feeling inadequate to the task, one day I told him, "Jesus is in your heart." We had been singing together along with a tape, "Thank you, thank you, Jesus in my heart," when I said, "Dragen, Jesus is in your heart."

Dragen looked away, as if disturbed, then moved into the corner of our tiny room and faced the wall. After a minute or so with his back to me, finally, he turned to face me.

"I can't see my heart," he said.

I went home that night thinking about his words. It came to me that I would need to create a visual metaphor to help him understand.

At an office supply store, I found a blank triptych that stood about as tall as he was. I pasted one half of a large red foam-board heart onto each door. Inside, on the center panel, I pasted an icon of Jesus and taped a wooden cross above it.

Dragen was delighted. He knocked on the doors of the heart saying, "Knock, knock. Who is it? It's Jesus." Opening and then folding the doors of the heart around himself, he was in Jesus' heart, just as Jesus was in his. One day some months later, quite spontaneously, he took a small wooden cross from the table and, pretending it was a key, applied it to the red foam heart. It was as if he knew somehow that the cross was the key to Jesus' heart and the key to opening his own. I was astonished. He had taken the visual metaphor and run with it.

The homemade triptych was only the beginning. I began to create more and more tangible materials for him. I realized then that something extraordinary was happening. While the "facts and concepts" of the faith seemed almost meaningless to him, the most spiritual aspect, the inner core of our faith, seemed to affect him deeply. We were communicating in the language of the psalms, using images and metaphors that allowed Dragen to articulate what he already knew of God himself. I was merely giving him a language to express it.

He loved our time together. "Is today Monday?" (our day), he would ask his mother each morning. He was growing and thriving spiritually, and so was I. My time with Dragen was launching me directly into my own experience of God-away from the linear, logical formulations of dogma, so often causing more confusion than clarification. Here on the boundary between this "other" person and myself was where I found God in a unique way. Dragen was moving me away from my head, from my academic training in calculus, chemistry and biology, from my years as a medical writer, into a deeper experience of God, beyond mere logic.

Pain and the Cross

Dragen and I were developing a wonderful relationship, learning to encounter God together. When I was with Dragen, I began to experience God as I did at no other time and in no other way.

Nevertheless, a cloud hung over our sessions. From the beginning Dragen's mother had warned me that the doctors did not expect him to live long. Along with the Down syndrome and an array of other medical problems, Dragen was born with his bladder outside his body. Within hours of his birth the first of many drastic, life-saving operations had begun.

Pain was something Dragen knew all too well. Sometimes he would lie down on the carpet of our little room. "Does Mary love me? Does Jesus love me?" He was reciting "the pain litany," letting me know that he was in pain, although he rarely complained, short of screaming when it became unbearable.

At the end of that first year, when he had just turned 7, Dragen underwent major surgery again. I went to visit him at home after a particularly lengthy hospital stay. It was a steamy August day; he answered the door in his underpants. I had brought along a tape recorder with one of his favorite tapes, "Jesus, Remember Me." He took the recorder and disappeared into his bedroom, reappearing minutes later. He was holding the recorder to one ear, the music playing full volume. In his other hand he held a crucifix high over his head. Around his neck he had tied a towel, which was hanging down his back like a cape. Around and around the room he marched, singing. He was the priest, the choir, the altar server, the congregation—the whole church. He missed attending Mass, I realized.

After a while he went over to the sofa, lay the crucifix down, and began loosening the nails from Jesus' body. He pried Jesus off the cross and kissed him, whispering, "I love you, I love you." He was giving Jesus a break from the pain.

Not long after Dragen's operation, his mother told me, she had come into his bedroom and found him naked on the bed, his arms outstretched. "What are you doing?" she asked. "I'm Jesus," he answered, pointing to the new stoma surgically implanted in his side to accommodate a catheter. He was identifying with Jesus, wounded in his side, as he hung naked upon the cross. The cross had a profound, personal meaning for Dragen.

Dragen had entered into the metaphor of the crucifixion and was living out of it. By participating in his own crucifixion, he was also entering into the Great Crucifixion. Through the door of the particular, he was entering the universal. I saw then a child with mental disabilities experiencing God with all of his being.

When I began working with Dragen, my job was to "make a case for God" to a little boy with disabilities, yet over time it became apparent that he already knew God. But now, paradoxically, the task of making a case for God was shifting back onto me. It was becoming a personal question-how to make a case for God to myself in the face of suffering? Specifically, why does a loving God permit an innocent child like Dragen to suffer? Does such a God exist at all?

I had come to faith as an adult in a time of intense emotional pain. My childhood was also intensely painful. And I began to see that a lifetime of spiritual and emotional suffering had prepared me for this encounter with Dragen. From my own childhood I knew how "otherness" felt. Somehow I knew what it was like to be a child with Down syndrome in a culture that all too often regards people like Dragen with withering glances, that tosses out careless, unkind remarks, which are not lost on someone as sensitive as he is.

My own pain, transformed, was now a gift. It enabled me to see something in the core of Dragen's being that was so magnificent I wanted to shout it out to a mostly deaf and blind world. My own pain had enabled me to draw closer to Dragen, to transcend the boundaries of doctrine and enter into the heart of God, where I had had to let go of the question of suffering and simply live out the tough day-to-day reality of it.

Surrender

Dragen turned 16 years old this spring; the doctors say he has far outlived their expectations for him. At last count he had had over 50 operations, including, most recently, a kidney transplant. I have been with him now for 10 years.

Each time he goes into the operating room he seems completely stoic. "'Be brave, Dragen. It goes better that way.' That's what Poppy [his grandfather] told me," he said once, sitting up with the surgical cap on his head as he was being wheeled in on a gurney. He seems to know in his deepest elemental being the truth of Christ, not just about him. It appears that Dragen has completely and totally surrendered to God, while I still rail and question: God, what are you doing? Or I cry out: O God, please take him home; spare him more pain.

Over the last few months Dragen's health has been deteriorating. When we are together we talk of his own death now. We visit each other frequently. On the days Dragen comes to my house, typically we go to the cemetery. His grandmother, "Nanny," died nearly five years ago now, and he still misses her terribly. We sit on the grass in the graveyard in front of her tombstone, and we pray and sing together with a tape recorder blasting full volume, "Alleluia, He Is Coming."

"Look at all these people who will welcome you into heaven." I say, my hand sweeping around, indicating all the tombstones. "Hooray, Dragen! We are so happy to see you!" they will say; and Dragen claps his hands and grins, delighted.

After one such visit, Dragen asked me to write him a letter about death. I wrote...

Dear Dragen,

Remember when you asked me, "Write me a letter about death"? I didn't forget. So here is your letter about death.

In the Bible it says, "The Lord, our God, holds the keys of death." This is true and real. This is what God promises us. And Jesus promises us. And Jesus always tells the truth. Because he is truth, he cannot lie.

When it is time to die, Jesus will come with a key to the door of death. He will open the door and then together with the angels and saints and Mary, the Blessed Mother, you will float up over the rooftops and trees and everything, and you will just float up to heaven with Jesus. You can just relax, because Jesus will do it for you.

It is good to die. Everybody is going to die. But only God knows when it is time for you to die. He knows the right time, and then he sends Jesus with the keys to the doorway. God knows what is best for each person.

The Bible tells us that heaven is the holy city of God. It is where God is living with all the people who belong to God, like Nanny and Poppy and Christina and Richard. God is always there with them. The Bible says there is no crying in heaven. No more sadness. And there will be no pain in heaven. In heaven God will make all things new—including your body! You will have a new body in heaven.

God loves you so very much, Dragen, more than 480 large houses! You will be so very happy with him.

Who will cry when you die? Most of all, Mommy will cry because she will miss you. Your Dad will cry. Aunt Jeanie, Aunt Dede, Aunt Dottie, your cousins, Cathy and Walter, Father Bob, Sister Mary Frances, your friends and teachers, the bus driver, the doctors and nurses and your aides will cry. And of course, I will cry.

But then we will remember that Dragen will have no more pain and Dragen will have a new body in heaven! And then we will remember that Dragen will be so happy to see Nanny and to see Jesus and Mary. And that thought will comfort us and make us smile. We will hold you close to ourselves in our hearts. We will still feel you with us, and then when we die, we will all be together!

I love you,

Miss Lyn

Dragen's suffering has drawn me into the tangible, living crucifixion of Jesus where I am crucified myself and humbled and where all my questions melt away. Yet as I enter into the crucifixion with Dragen, somehow, paradoxically, I am able to catch a glimpse of the compassionate God.

Here is where God resides—on this boundary between "the other" and myself. I do not confuse Dragen's gifts with my gifts, but rather I am able to participate in his gifts just as he is able to participate in mine. My own gifts are honed in the process; my love becomes so much bigger than myself. Here, too, I become more compassionate. I am, therefore, living a transcendent life on this border between myself and Dragen. Is this not God—Jesus himself living in me, living in Dragen, in this place where we meet?

The only way I know to articulate this encounter is in the language of poetry.

I feel the dimensions of truth in image—"the keys to the doorway of death," the verse from the Psalms. I can see the keys, I can hear them jingling on a key chain, I can feel them cold against my skin and taste the metal on my tongue. This image engages all of my being, as my own death will also do. This biblical description of death is truth, albeit not on a literal level, but it is a truth that carries me beyond a merely logical mindset, away from an arid, thirsty land without hearing and seeing, without feeling, without music, without singing—and without poetry.

"Write me a letter about love?" Dragen asked me the last time we were together.

"Dragen, here is your letter about Love."

Lyn Burr Brignoli teaches religion to children with Down syndrome, autism and other cognitive disabilities at St. Mary Catholic Church in Greenwich, Conn., where the events described in this article took place.

Cinquantenaire de la trisomie 21. Retour sur une découverte

Médecine Sciences 2009; 25 (3): 311-5

Marthe Gautier

6, rue de Douai, 75009 Paris, France.

marthe.gautier@free.fr

Permis d'imprimir: François Flori, Editorial Manager, EDK Publisher Médecine/Sciences

« En réalité, les découvertes sont dues à des personnes en marge des groupes de chercheurs formatés. »

Pierre Laszlo

Il y a cinquante ans, j’étais cosignataire1 de l’article

princeps qui établissait la présence d’un chromosome

surnuméraire [1] dans le syndrome individualisé par

Langdon Down en 1866 et communément appelé alors

en France « mongolisme ». C’était la première aberration

chromosomique autosomique reconnue dans

les cellules de l’espèce humaine; elle reçut le nom de

trisomie 21. Il m’a semblé historiquement intéressant

d’apporter mon témoignage personnel en tant qu’acteur

de cette découverte.

Rappel historique

Se situer en 1958 implique de retrouver le contexte et

les certitudes de l’époque. Alors qu’il était admis depuis

plusieurs décennies que l’espèce humaine possédait

48 chromosomes, J.H. Tjio et A. Levan [2] démontrent en

1956 qu’il n’y en avait que 46. Ceci affecta peu de gens – hormis quelques généticiens – et pendant longtemps le

chiffre de 48 fut enseigné dans les écoles. L’étape qui

paraissait simple fut suivie d’autres plus importantes

nous entraînant vers la connaissance des origines de

la vie; elle ne fit pas le même bruit médiatique que la

mise en orbite du premier satellite artificiel, le Spoutnik

(en russe, compagnon de voyage) quelques mois plus

tard. Ce vol contribua à nous conduire vers l’origine de

l’univers. La science avance différemment au hasard

des disciplines.

Il avait fallu attendre 30 ans avant que ne soient transmises

aux biologistes les lois génétiques des petits pois

de Johan Mendel, ou frère Gregor au couvent des Augustins

de Brno; nous sommes en 1900. La même année,

Nettie Stevens met en évidence l’existence des chromosomes

sexuels chez un coléoptaire [3]. Vers 1910, les

travaux de Morgan sur la drosophile, cette providentielle

mouche du vinaigre qui se reproduit très vite et présente

des chromosomes géants, inaugurent les débuts de la

cytogénétique [4]. S’il n’y avait eu l’attitude d’Alexis

Carrel (Prix Nobel en 1912) pendant la période de l’Occupation

[5], son expérience des cultures cellulaires

eût pu être alors largement utilisée. Mais, une longue

suite d’erreurs et d’échecs découragea les chercheurs.

Et ce n’est qu’en 1949, et uniquement sur les cellules

d’épiphyse de chat, que Barr et Bertram [6] découvrent

l’existence d’un corpuscule dans le noyau des femelles;

il s’agissait en fait d’un phénomène général qui signait

la présence de deux chromosomes X. L’explication cytologique

(lyonisation) en revint à Mary Lyon [7]. Le simple

frottis de la muqueuse buccale permit alors d’aborder

les diagnostics des états intersexués.

La découverte de la trisomie 21, telle que je l’ai vécue...

Les prémices

J’arrive à Paris, en 1942, en pleine guerre, près de ma

soeur aînée Paulette, interne à l’Institut Gustave Roussy,

en fin d’études de médecine. Elle m’initie aux arcanes

du statut d’étudiante. Elle me met en garde: « Quand

on est une femme, qu’on n’est pas fille de patron, il

faut être deux fois meilleure pour réussir ». J’aborde

le PCB (prépa de médecine): facile. En 1944, Paulette

est tuée par des Allemands en débâcle, au moment de la Libération. Pour mes parents, dans leur chagrin, dès ce moment, il a fallu que je sois à la fois elle et moi: difficile. Mon objectif, les concours qui ouvrent les portes. Après l’externat, je réussis l’internat des Hôpitaux de Paris (IHP), tant convoité et, à l’époque, peu féminisé (les femmes n’y ont eu accès qu’en 1885). Dans ma promotion, sur 80 internes nommés, il n’y a que deux filles.

Après quatre ans d’un merveilleux apprentissage clinique en pédiatrie,

un de mes maîtres, le Pr R. Debré, pape de la pédiatrie, me propose une

bourse d’un an à Harvard, offerte par un mécène qui venait de fonder

la SESERAC2. Objectif: la cardiologie infantile pour: (1) éradiquer

la maladie de Bouillaud ou RAA (rhumatisme articulaire aigu) par la

pénicilline et traiter les cardites parfois mortelles par la cortisone,

encore peu disponible en France; j’avais consacré ma thèse à l’étude clinique et anatomopathologique des formes mortelles de cette affection

due à l’agression du streptocoque A bêta-hémolytique, germe

resté très sensible à de faibles doses de pénicilline, qui n’était arrivée en Europe que tardivement, après la guerre; (2) créer un département pour le diagnostic et la chirurgie des cardiopathies congénitales du nouveau-né et du nourrisson. Perspectives nouvelles et fascinantes:

apprendre pour mieux soigner et guérir des enfants...

Après quelques hésitations, j’accepte, non sans réticences: quitter

amour, amis, famille pour un an, sans se revoir, ni se téléphoner (trop

coûteux à l’époque). Mais ma décision est prise: en septembre 1955,

le trajet en train Paris-Le Havre se fait dans les larmes. On embarque

la cantine sur le Mauritania de la compagnie Cunard (l’avion est bien

trop onéreux pour des boursiers). Par chance, deux collègues amis IHP,

pédiatres de l’école Robert Debré, Jean Aicardi et Jacques Couvreur3,

boursiers Fullbright, sont du voyage et, par chance, aussi basés à Boston.

Nous sommes les premiers IHP à bénéficier d’une bourse d’étude

aux États-Unis.

Plus de cinq jours en mer; une toute petite tempête; et lentement, au

petit jour, l’arrivée. Les hélices se taisent doucement. Les gratte-ciel de

Manhattan se découpent sur un ciel merveilleusement bleu. Nous sommes

les hôtes de l’oncle Sam. Bien qu’imparfaitement bilingues, nous ne

sommes pas des émigrés « sans-papiers ». Nous avons un visa d’un an.

« As a pilgrim » I am in Boston

Vingt-quatre heures pour trouver un appartement en co-location, acheter

un lit, une chaise et une table aux puces locales. Le Pr David Rutstein

a prévu un programme parfait: chez le Pr Alexander Nadas, pionnier du

diagnostic des cardiopathies congénitales (CC) avant chirurgie et chez le

Pr Benedict Massell, responsable du RAA. Je visiterai aussi plusieurs centres

spécialisés sur le RAA: Cleveland, Chicago, San Francisco, Seattle,

la Nouvelle Orléans, Washington. L’accord était en effet loin d’être fait sur la dose de cortisone à prescrire et sur la durée du traitement. On se

demandait aussi si cette drogue « miracle » pouvait prévenir l’apparition des cardites. Les responsables de chacun de ces centres

m’ont fait partager leur expérience et leurs opinions, qui,

dans leurs divergences même, m’ont beaucoup appris.

Ce voyage sera effectué bravement, en solo, dans les

autobus Greyhound (plus de dix nuits pour économiser les

frais d’hôtel, mais les bus sont bien supérieurs aux avions

pour apprécier le paysage...).

Un autre « job » m’est assigné que j’ignorais: technicienne

dans le laboratoire de culture cellulaire

(fragments d’aorte). C’est un plus. À temps partiel,

à mon gré, éventuellement le dimanche. Qu’à cela ne

tienne. Une charmante technicienne m’apprend tout

ce qu’on doit connaître en culture cellulaire, et en

plus elle m’initie au . Tout est à portée de main

dans un congélateur. Je savais surveiller les cultures

au microscope, les prendre en photos et développer

celles-ci. Je constitue des dossiers pour les biochimistes

qui font des études comparatives des taux de

cholestérol dans les fibroblastes d’enfants et d’adultes.

Je remplace la responsable du labo en congé de

maternité. Je fais des séjours prolongés à la grande

bibliothèque située à l’étage. J’explore les diverses

techniques de cultures cellulaires, les données

récentes en cardiologie. Mais à l’époque, rien sur la

génétique ne m’a interpellée.

La bibliothèque est un lieu de rencontres et d’échanges.

Nous, Français, sommes perçus comme issus d’un pays

sous-développé, qu’il faut toujours aider à terminer ses

guerres, et qui s’emmêle en Algérie! Depuis, je plains et

défends tous les immigrés du monde.

Mon visa expire enfin. Retour sur le Flandres. J’ai honoré

ma dette vis-à-vis de mon mécène et reviens pleine

d’enthousiasme et de projets. J’arrive au petit jour

au Havre. On m’attend sur le quai...

À Paris, il faut reprendre ses esprits.

Nouveau décor

Le poste de chef de clinique promis chez le Pr M. Lelong

avant mon départ a été donné à un collègue en mon

absence. Seuls postes disponibles: à l’hôpital Trousseau

chez le Pr R. Turpin chez qui je n’ai jamais été ni stagiaire,

ni externe, ni interne. Nous ne nous connaissons pas. Je ne

suis pas une élève de la maison! Avec l’ami Jean Aicardi,

qui revient lui aussi de Boston, nous voilà « chefs » en

septembre 1956. Le clinicat est un poste d’enseignement

à mi-temps, peu rémunéré, mais obligatoire pour monter

vers l’assistanat et le médicat. L’atmosphère est celle

d’un service hospitalier, figé dans sa hiérarchie typiquement

française, et dont le patron est peu communicatif

et très distant. Quel contraste avec l’atmosphère décontractée

des États-Unis! Mais il faut « faire avec », avant

de prendre son essor ailleurs et de gagner sa vie.

Pédiatres avertis, nous savions que ce patron s’intéressait

aux états malformatifs: tenter de distinguer l’inné

de l’acquis. En 1937, il avait évoqué dans le mongolisme

la possibilité d’une anomalie chromosomique proche de

celle de la mutation Bar de la drosophile [8]. Il n’était

pas le premier, ni le seul à faire ce type d’hypothèse,

mais n’était pas allé plus loin à ce jour. Il s’était tourné vers l’étude des dermatoglyphes, un pis-aller de fortune,

dans les recherches sur l’hérédité du mongolisme.

En 1950, à Londres, L. Penrose [9] penchait plus pour

une triploïdie que pour une trisomie ou une monosomie.

Il a l’occasion d’avoir un échantillon testiculaire de

patient qu’il confie à Ursula Mittwoch. La technique et

les résultats sont incertains: elle conclut que les cellules

ont « 47 ou 48 chromosomes », à une époque où le

nombre normal dans l’espèce humaine était estimé à 48. Mais du moins la triploïdie était exclue.

Le déclic

Donc, à la rentrée 1956, le Patron, revenant du Congrès

International de Génétique Humaine à Copenhague,

nous apprend que le nombre de chromosomes de l’espèce

humaine n’est pas de 48, mais de « 46 »; il dit

alors regretter qu’il n’y ait pas à Paris de lieux où faire

des cultures cellulaires pour pouvoir compter les chromosomes

des mongoliens. Surprise par cette remarque,

je m’en étonne et, forte de mon expérience américaine,

je propose « d’en faire mon affaire, si l’on me donne

un local ». Je sais qu’il faut agir vite, sans se tromper,

et réussir les premiers, car les équipes internationales

vont ou sont déjà entrées en compétition, rivalité habituelle

dans le domaine de la recherche, comme ailleurs.

Je m’inscris en Sorbonne au certificat de biologie cellulaire.

Je réalise qu’il ne faut pas compter sur l’aide des

organismes de recherche, la France n’étant pas encore

remise de la guerre, à peine en voie de restructuration

avec l’INH4. Enfin, sciences et politique ne font bon

ménage que quand finances il y a, ce qui n’est pas le

cas. Le rôle de l’Université était celui de l’enseignement

clinique; elle n’était pas armée pour une recherche

pointue. L’élite hospitalière n’avait pas encore

compris qu’il lui appartenait de donner l’impulsion.

Un local vide est enfin mis à ma disposition, ancien labo

de routine non utilisé. Trois pièces magnifiques, un frigidaire,

une centrifugeuse, une armoire vide en haut de

laquelle se trouve un microscope à faible définition. Eau,

gaz, électricité. Et seule pour tout organiser, un rêve! Je

suis peu fortunée et aucun crédit de fonctionnement ne

m’est proposé. C’est donc à mes frais, avec un emprunt, que je m’équipe en verrerie, appareil à eau distillée, etc. Aucun des

produits nécessaires à la culture n’est commercialisé en France. Déterminée, je ne baisse pas les bras. Je prépare chaque semaine l’extrait

embryonnaire frais, à partir d’oeufs embryonnés de 11 jours que je vais

chercher à l’Institut Pasteur. Pour le plasma, je ponctionne le sang

d’un coq que j’ai acheté et qui est élevé dans un jardin à Trousseau. Et comme sérum humain, c’est le mien, procédé économique et sûr. Tout ceci a été exposé [10]. Je ne veux utiliser ni le poumon foetal, ni les cellules de moelle osseuse, mais des explants de tissu conjonctif dont

j’examine les cellules très jeunes in situ, en transplantant l’explant

quand la pousse me paraît suffisante. Pas d’antibiotiques. Jamais de

colchicine, car je redoute un éventuel effet néfaste sur l’intégrité du caryotype. Pas non plus de subcultures après trypsination, pour éviter

des anomalies acquises in vitro par des cellules transformées. J’estime

cela indispensable pour éviter tout artéfact, tel que chromosome erratique

ou induit. Il faut faire preuve d’initiative, d’imagination et de

discernement en cas d’échecs.

Ensuite, j’utilise – en l’adaptant – le principe du milieu hypotonique qui

avait permis les résultats de Tjio et Levan [2], mais à base de sérum

pour ne pas rompre la membrane cellulaire, enfin en laissant sécher les

lames avant de les colorer [11]. Jamais de squash, préconisé par certains

[12]. Ainsi, mes plus belles préparations sont en prométaphase,

sans rupture de la membrane cellulaire, ce qui permet un chiffre exact

et de très beaux chromosomes allongés, faciles à apparier, non cassés.

Ces résultats ne sont acquis qu’après certains échecs. Je ne disposais

d’aucune bibliographie, mais seulement de mes notes prises à Boston.

Les témoins, que me procure le service de chirurgie voisin, proviennent

d’interventions chirurgicales programmées chez des enfants normaux.

Ils ont 46 chromosomes. J’ai maintenant deux techniciennes AP (Assistance

Publique) qui, instruites par mes soins, sont remarquables5.

Je leur transmets le doigté et l’expérience.

|

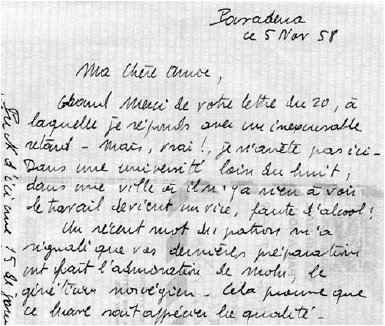

| Figure 1. Service du professeur Turpin en 1957. Au premier rang; première à gauche, Marthe Gautier, troisième, Jacques Lafourcade, cinquième, professeur Raymond Turpin. Au second rang, premier à gauche, Jean Aicardi. |

|

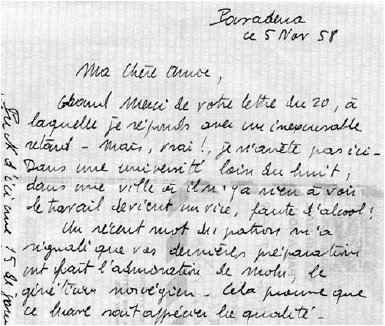

| Figure 2. Photocopie d’une lettre envoyée par J.L. pendant son voyage aux États-Unis. Il m’écrit « vos préparations... » c’est-à-dire les lames que j’avais obtenues avec les premières mitoses à 47 chromosomes. |

Un nouveau venu au laboratoire

Je ne me souviens pas avoir eu au début de visites du patron. En revanche,

son assistant Jacques Lafourcade passait me voir, un peu intrigué

et au début sceptique sur l’éventualité d’une réussite de l’aventure, surtout dans les conditions précaires où elle était tentée. Sans doute rendait-il compte de l’évolution de mon travail.

Mais, je reçois bientôt des visites répétées de J. Lejeune. J.L., que je ne connaissais pas, était stagiaire au CNRS et élève du patron, comme en

témoignent leurs publications communes sur les dermatoglyphes et l’effet néfaste des radiations ionisantes [13-16]. Je comprends vite l’intérêt qu’il porte aux cultures cellulaires, abandonnant sa loupe et ses statistiques sur la fréquence du pli palmaire médian.

Des tissus d’enfants mongoliens sont enfin obtenus6. En mitose, les

cellules de mongoliens ont indiscutablement une différence: elles

ont toutes 47 chromosomes, alors que tous les témoins en ont 46.

J’ai gagné mon pari, celui de réussir seule avec mes laborantines une

technique et surtout de mettre en évidence une anomalie. C’est une

découverte française. Cela n’était pas évident au départ.

Le chromosome supplémentaire est petit, le labo n’a pas de photomicroscope

qui permettrait d’attester de sa présence et d’établir le

caryotype. Je confie les lames à J.L. qui fait faire les photos, mais ne

me les montre pas: elles sont, me dit-on, chez le Patron. Elles sont

comme séquestrées. Ce chromosome ressemble au 21, mais il ne sera

baptisé comme tel qu’à la conférence de Denver en 19607.

Je suis consciente de ce qui se dessine sournoisement,

mais n’ai pas assez l’expérience ni d’autorité dans

ce milieu médical dont je n’ai pas encore compris les

mécanismes pour savoir comment m’y confronter.

Trop jeune, je ne connais pas les règles du jeu. Tenue

à l’écart, je ne sais pourquoi l’on ne publie pas tout

de suite. Je n’ai compris que plus tard que J.L., inquiet

et n’ayant pas l’expérience des cultures, craignait un

artéfact qui aurait brisé sa carrière – jusque-là assez

peu brillante – mais qui, si les résultats étaient avérés,

s’annonçait soudain géniale. Je soupçonne des manoeuvres

politiques... je n’avais pas tort. En revanche, personnellement,

je n’avais pas l’intention « d’exploiter »

ce chromosome surnuméraire, ma vie professionnelle se

construisait ailleurs, vers la clinique.

Désormais, J.L. va se présenter comme le découvreur de

la trisomie 21. Rapporteur CNRS au congrès des radiations

ionisantes au Canada et, sans que cela soit prévu

avec Turpin ni, bien sûr, avec moi, il parle de la découverte

au séminaire McGill (en octobre 1958) comme

s’il en était l’auteur. Je reçois cependant cette lettre

datée du mois suivant pendant qu’il visite des labos aux

États-Unis (Figure 2).

À ce moment, J.L. a été mis au courant des travaux de

Patricia Jacobs qui venait de trouver dans le syndrome de

Klinefelter un chromosome X surnuméraire [17, 18]. Dès

son retour, nous publions enfin, et cette fois en urgence,

à l’Académie des Sciences, pour devancer inélégamment,

en date, les équipes anglo-saxonnes [19]. Sans que j’aie

pu encore voir les photos, sans avoir été informée de

quoi que ce soit. Le texte m’est oralement communiqué

un samedi midi pour être présenté le lundi. Exception

française, car on pouvait, en effet, publier en trois jours

aux CRAS (Comptes Rendus de l’Académie des Sciences)

à Paris, alors qu’il fallait deux mois dans les journaux

internationaux. Nous sommes donc les premiers à publier

cette découverte dans le milieu scientifique international,

après en avoir parlé au séminaire McGill. Contrairement

à l’usage, J.L. signe en premier et mon nom ne figure

qu’en second. Conformément à l’habitude, le Pr Turpin,

chef responsable de l’hypothèse de départ, signe en dernier.

Je suis blessée et soupçonne des manipulations, j’ai

le sentiment d’être la « découvreuse oubliée ».

Un grand vacarme médiatique est alors orchestré par J.L. qui est interviewé par tous les journaux. Une grande

découverte française... Dès lors, J.L. est couvert de

récompenses; de stagiaire au CNRS, il est promu maître

de recherche, médaille d’or. Sans avoir suivi le cursus

universitaire, il sera ensuite nommé professeur de cytogénétique,

poste créé par le Pr Turpin pour son élève.

Cette chaire va ouvrir l’ère de la cytogénétique en France,

tandis que cette discipline se développe partout dans le monde et que s’étend la renommée de J.L. Il reçoit le

prix Kennedy, sans demander que j’y sois associée. Progressivement

et en participant à de nombreux congrès,

il se présente comme le seul découvreur et finit par s’en

convaincre, à tel point que les héritiers du Pr Turpin s’en

émurent juridiquement par voie d’avocat. Ils déposèrent

en outre dans les archives de l’Institut Pasteur les articles

de leur père attestant son antériorité dans l’hypothèse

chromosomique du mongolisme, enfin vérifiée. Pourtant,

désormais, « le père de la trisomie 21 » comme le présentent

désormais les médias, devient une sorte de thaumaturge8

dont les tentatives de traitement de la trisomie 21

laissent sceptiques de nombreux scientifiques, car elles ne

reposent pas sur des mécanismes biochimiques crédibles.

Par la suite, et dans une continuité très cohérente, à

la fin des années 1960, le diagnostic prénatal devient

possible; puis, en 1975, est votée la loi sur l’avortement

qui va susciter chez J.L., croyant intransigeant,

indignations, batailles et polémiques. Elles attiseront

de graves querelles dans la société et provoqueront un

réel désarroi parmi les cytogénéticiens dont certains

souhaitaient que le diagnostic prénatal soit pratiqué

en France. À ce moment, comme le mentionne André

Boué9, le comité Nobel aurait envisagé de récompenser

la découverte de l’origine du mongolisme. Est-ce en

raison de ses prises de position que le prix Nobel n’a

pas été attribué à Jérôme Lejeune, seul nom qu’avaient

fait résonner les trompettes de la renommée?

Épilogue

Première anomalie autosomique humaine ou première

anomalie gonosomique, à Paris ou à Edinburgh, ces

trouvailles furent faites de façon concomitante, comme

c’est souvent le cas quand sont atteints les niveaux

scientifiques et technologiques. Si je n’avais été la première,

d’autres y seraient parvenus. Quoi qu’il en soit,

je n’ai gardé aucun souvenir agréable de cette période,

tant je me suis sentie flouée à tous égards. Mais

dans l’histoire des « découvrances », combien d’autres

furent ainsi passés sous silence, comme le Bâlois Johann

Friedrich Miescher ou la Britannique Rosalind Franklin, pour ne parler que de l’ADN.

Depuis, la génétique moléculaire a vite rattrapé et

dépassé la cytogénétique. Nous connaissons à présent

la carte physique du chromosome 21 avec 225 gènes –

dont 127 seulement sont aujourd’hui identifiés – et sa

séquence, réalisée en l’an 2000.

Depuis, également, la considération pour les femmes scientifiques a

sans doute progressé, puisqu’en 2008, le prix Nobel a été décerné non

seulement à Luc Montagnier, mais aussi à Françoise Barré-Sinoussi

pour leurs travaux sur la découverte du rétrovirus responsable du sida

[20]. Un espoir pour l’avenir.

SUMMARY

Fiftieth anniversary of the trisomy 21: Return on a discovery

Fifty years ago, I was co-author of the first paper asserting the presence

of a supernumerary chromosome in Down’s syndrome (called

« mongolism » in France at that time). This first autosomal chromosomal

abnormality was called Trisomy 21. It seemed to me historically

interesting to bring my own testimony as an actor in this discovery.

REMERCIEMENTS

Je tiens à remercier Joëlle Boué et Simone Gilgenkrantz qui m’ont encouragée à faire resurgir ces très anciens souvenirs.

NOTE EN BAS DE PAGE

1 Par un lapsus calami que je n’ose interpréter, mon nom fut inscrit de façon erronée Marie Gauthier. L’erreur fut corrigée dans les publications ultérieures.

2 Un de ses enfants venait de mourir de maladie de Bouillaud, faute de cortisone en France et il avait fondé la Société d’Etudes et de Soins pour Enfants atteints de RAA et de CC.

3 Par la suite, Jean Aicardi fit une brillante carrière nationale et internationale en structurant la neurologie infantile; un syndrome porte désormais son nom. Quant à Jacques Couvreur, il partagea sa vie de pédiatre entre l’hôpital et la clientèle privée et fut le référent national dans le traitement des toxoplasmoses congénitales.

4 L’Institut national d’Hygiène avait été créé en 1941, et c’est seulement à partir de 1958 que des réformes sont entreprises.

5 Mmes Macé et Gavaïni.

6 Je suis alors très occupée: j’ai en charge à mi-temps à l’hôpital Bicêtre le service de crèche de CC (cardiopathies congénitales), les consultations de RAA, et le début de ma clientèle privée.

7 Ironie de l’histoire cytogénétique, après la classification à Denver en 1960, on s’aperçut par la suite que

ce chromosome était plus petit, donc correspondant à la 22e paire, mais tout resta dans cet ordre pour ne pas perturber la bibliographie déjà abondante sur le sujet.

8 Personne qui fait ou prétend faire des miracles.

9 Cf. Entretien André Boué, janvier 2001. Histoire de l’Inserm: http://infodoc.inserm.fr/histoire

RÉFÉRENCES

- Lejeune J, Gauthier Marie, Turpin R. Les chromosomes humains en culture de tissus. CR Hebd

Seances Acad Sci (Paris) 1959; 248: 602-3.

- Tjio HJ, Levan A. The chromosome number of man. Hereditas 1956; 42: 1-6.

- Gilgenkrantz S. Nettie Maria Stevens (1861-1912). Med Sci (Paris) 2008; 24: 874-8.

- Morgan TH, Bridges CB, Sturtevant AH. The genetics of Drosophila. Bibliographica Genetica 1925; 2: 1-262.

- Gilgenkrantz S, Rivera EM. The history of cytogenetics. Portraits of some pioneers. Ann Genet 2003; 46: 433-42.

- Barr ML, Bertram EG. A morphological distinction between neurones of the male and female,

and the behaviour of the nucleolar satellite during accelerated nucleoprotein synthesis.

Nature 1949; 163: 676.

- Lyon MF. Gene action in the X-chromosome of the mouse (Mus musculus L.). Nature 1961; 190: 372-3.

- Turpin R, Caratzali A, Rogier H. Étude étiologique de 104 cas de mongolisme et considérations sur la pathogénie de cette maladie. Premier congrès de la Fédération internationale latine des sociétés d’eugénisme, Paris: Masson, 1937, 154-64.

- Penrose LS. Value of genetics in medicine. Br Med J 1950; 2: 903-5.

- Lejeune J, Turpin R, Gautier M. Étude des chromosomes somatiques. Technique pour la culture de fibroblastes in vitro. Rev Fr Etudes Clin Biol 1960; 5: 406-8.

- Rothferls KH, Siminovitch L. An air-drying technique for flattening chromosomes in

mammalian oells grown in vitro. Stain Technology 1958; 33: 73-7.

- Hsu TC, Pomerat CM. Mammalian chromosomes in vitro. A method for spreading the

chromosomes of cells in tissue. J Hered 1953; 44: 23-9.

- Turpin R, Lejeune J. Analogie entre le type dermatoglyphique palmaire des singes inférieurs et celui des enfants atteints de mongolisme. CR Hebd Seances Acad Sci (Paris) 1954; 238: 395-7.

- Turpin R, Lejeune J, Génin Mlle, Lejeune B Mme. Recherche d’une éventuelle association entre l’hémophilie et certaines particularités des dermatoglyphes. Semaine des Hôpitaux de Paris 1955 (Annales de la Recherche Médicale, n° 3).

- Turpin R, Lejeune J. Effets probables de l’utilisation industrielle de l’énergie atomique sur la stabilité du patrimoine héréditaire humain. Bull Acad Natl Med 1955; 139: 104-6.

- Turpin R, Lamy M, Bernard J, Lefebvre J, Lejeune J. Nécessité de limiter l’exposition aux radiations ionisantes. Arch Fr Pediatr 1957; 14: 1055-6.

- Jacobs PA, Strong JA. A case of human intersexuality having a possible XXY sex-determining

mechanism, Nature 1959; 183: 302-3.

- Harper P. The beginnings of human cytogenetics. Paris: Scion, 2006: 200 p.

- Jacobs PA, Baikie AG, Court Brown WM, Strong JA. The somatic chromosomes in mongolism.

Lancet 1959; 1 (7075): 710.

- Costagliola D. Prix Nobel de Médecine 2008 (Françoise Barré-Sinoussi et Luc Montagnier): Une vie consacrée à combattre le Sida. Med Sci (Paris) 2008; 24: 979-80.

Web Wanderings

Down, Not Out. The Legacy of Jerome Lejeune and the Resurgence of Down Syndrome Research by Leticia Velasquez, NC Register, July 6-12, 2008. URL: http://www.ncregister.com/site/article/15354

Father's Journal

Paper Money

During Early Intervention friends and foes alike questioned our decision to raise Emmanuel bilingual. If they could see him now writing a thank you note in Spanish to his Mamá Grande for money received that she really should not have sent.

|

|

[...] Pope John Paul II recognized Lejeune's moral courage; the men were close friends and collaborators in fighting the culture of death. [...] He left this world saddened by his failure to find the cure for Down syndrome. But there is little doubt that he is still at work, interceding for his "little ones."

On June 28, 2007 the cause for canonization of Jerome Lejeune was introduced, signaling the heroic soul of this pro-life geneticist. Let us hope that his influence will continue to inspire the conscience of the medical profession to serve those with genetic syndromes, and not seek to destroy them.