|

Our group meets on the first Friday of every month at 6:30 p.m. at Saint Anthony's Wellness Center in the Alton Square Mall. For driving directions call the Wellness Center at 462-2222.

There will be no January meeting due to the holidays, but we encourage all families to attend the Down Syndrome Association of Greater St. Louis Christmas Party on Sunday, December 2nd, 1 - 4 p.m. High Ridge Elks Club, 101 Old Hunning Road, High Ridge, MO. Pictures with Santa, DJ with music, food, clowns, balloons, face painting, visits with Raggedy Ann and Andy and more! To help with planning for age appropriate goodie bags, please RSVP by November 26 to Lydia at DSAGSL office (314) 961-2504. For more information contact Sandy Munzlinger at (636) 271-6499.

Enclosed is a pamphlet from the Illinois Division of Specialized Care for Children (DSCC). Mary Trudell has kindly provided us with the following comments:

DSCC provides financial assistance for medical eligible services. DSCC does not pay for routine medical services and expects the family to utilize their health insurance first. The diagnosis of Down syndrome does not make an individual eligible for assistance from DSCC, however, many of the medical conditions associated with Down syndrome may be eligible. For example, our daughter Kate's diagnosis of strabismus qualified her for DSCC assistance. DSCC also reimburses for meals, when appropriate, and transportation costs.

A case worker, who is a registered nurse, works closely with the parent to authorize doctor visits and ensure the family is operating within DSCC guidelines.

STARNet Region IV

November 27 & 28. Family Conference on Wheels. Join us for a unique Family Conference that will explore the many resources available in Springfield to families of children with disabilities.

|

|

Participants will board a chartered bus at four locations in Southern Illinois. Cost: $25. Signature Inn double occupancy rates are $65. Contact: Sharon Gage, 397-8930, ext. 169, or Gary Dozier, ext. 171, E-mail: gdozier@stclair.k12.il.us.

January 9, 2002, 9:00 a.m. - 3:00 p.m. Special Education Rules: Answers and Questions. Location: St. Clair County Regional Office of Education, Gallery, Belleville, IL (Gallery). This program will address recent changes in special education statues and regulations and how they affect services for children up to age 8. Areas of focus include identification of children needing services, transition between early intervention programs and public school programs, what is really supposed to happen in special education staff meetings, how to create good communication avenues, and what records parents need to maintain. Presented by Vaughn W. Morrision, MS Ed and MSW and was employed by the Illinois State Board of Education (ISBE) for 26 years. Contact: Gary Dozier, 397-8930, ext. 171, E-mail: gdozier@stclair.k12.il.us.

Down Syndrome Articles

Down's Syndrome: Current Research by Jérôme Lejeune. Catholic Medical Quarterly. Feb. 1996. Vol. XLVI, No. 3 (269) p. 21-6. Reprinted with the permission of the editor, Peter Doherty, MRCS, DTM. &H, E-mail: office@cathdocs.freeserve.co.uk.

It is a great pleasure for me to speak to people who love Down's children. I mean children affected by Down's Syndrome. There is no such thing as a Down's person but human persons are affected by a very special disease which is due to an excess of a good thing. The chromosome 21 in trisomy 21 is in triplicate instead of in duplicate. But what is written on that chromosome is perfectly normal. The children with Down's Syndrome suffer from having an excess of good things; and the curious fact is that a good chromosome will give you trouble if there is too much of it. What I want to discuss with you is first, how we can figure out the intellectual damage resulting from this extra chromosome, and secondly- a corollary -how can we help to diminish the deleterious effect of the extra chromosome.

|

moonlight is the newsletter of the Riverbend Down Syndrome Association. It is made possible by the William M. BeDell Achievement and Resource Center, 400 South Main, Wood River, IL 62095, (618) 251-2175.

Editor: Victor Bishop

Web Site: http://www.riverbendds.org/

|

|

It is now more than 30 years ago that I saw the extra tiny chromosome for the first time. If I did a rough calculation, I would say that, then, for a baby conceived, and having an extra chromosome of the number 21, the probability of reaching 10 years of age was a little greater than it is today, because today some of them will be killed by abortion or by deliberate neglect at birth if they have some abnormality in the gut or the heart. They will not be operated upon and will die. I am afraid that infanticide is increasing where babies are affected by any kind of abnormality. Our once civilised countries are becoming harder and harder when it comes to respecting their own handicapped members. It may be that Down's Syndrome could be the first disease in which we could reverse the effects of the chromosomal imbalance we have seen over the last 30 years. And I will try to tell you how it could happen. However, it has not yet happened, but I hope research and clinical trials will soon show us a definite way to improve treatment and management of Down's Syndrome.

When there is an excess of a given piece of a chromosome, it produces a change in the phenotype, which means the development of the embryo is a little different from the standard. The typical Down's child has partly slanted eyelids, a round face and short hands. Every child has short hands and short fingers but Down's babies' are shorter. They are also more floppy than normal babies and have a kind of languor which makes them very attractive despite the fact that they are denied the intellectual maturity which is the greatest gift of our genetic patrimony.

The clinical features of Down's Syndrome are the same whether or not the baby is Chinese, African or Australian. To go deeper into cytogenetics, it can be shown that, although a mother may be perfectly normal, the baby has Down's Syndrome because it has inherited a very rare translocation. In this particular case, the mother had lost part of the end of chromosome 21 which was translocated onto the top of chromosome 18. However, she transmitted the translocated chromosome and the small 21. Therefore, the baby has got the tiny chromosome and also the extra piece on the top of chromosome 18. So he has received from the mother the two parts of the rearranged 21. He received a normal 21 from the father: and so the baby has full blown Down's Syndrome. This is an example of how we can analyse the chromosome. Different families, although they are very rare, can have some translocation at a different place, so that by chance some babies will only have that little piece in excess. We will look at that little piece but not the entire chromosome 21.

The only general phenomenon I would bring to your attention is that we have an aspect of type counter-type. That is, if a baby has an excess of this part of chromosome 21, he will have full Down's Syndrome but if he has lost this same part he would have the opposite of Down's Syndrome. Instead of having small ears he would have big ears and instead of having short fingers he would have slender fingers. The phenotype would be the opposite of Down's Syndrome. In most of the other abnormal allocations of chromosomes in man, the lack of a given segment of the genome, no matter what chromosome it comes from, gives a typical picture which is more or less the opposite of the picture that the excess will give. This gives us the first indication that the segment is the cause of the disease.

Now the second phenomenon is that, when it comes to intelligence, any lack or any excess of a chromosome gives the same result: it diminishes the performance, in other words it decreases the intelligence. It is very curious that excess of one gene could produce a crooked little finger, or the lack of it a very slender finger; a type-counter type picture: although, when it comes to the mind, the result is always very serious and damaging. Now to understand that, we can only use a metaphor because a full demonstration would be very very cumbersome. The metaphor is very simple: Human intelligence is very similar to a symphony. Genes are comparable to the musicians of an orchestra. If the orchestra delivers the full symphony, all of the musicians have to read their score exactly and to follow the tempo of the conductor. Now let's look at one musician who plays faster than he should. It depends whether he is playing alone in a solo or whether he is playing in a tutti, when all the instruments are playing together. If he is playing a solo, if he plays too fast, he will change an andante into a prestissimo, the change will be very localised and it will not spoil the symphony. It will just change the tempo imperceptibly. On the other hand if he is playing in a tutti with all the musicians playing together then it does matter whether he goes too slowly (in the case of the lack of a gene) or too fast (in the case of trisomy); he will spoil the result because the tutti is played with the help of all the musicians. If one of them plays the right notes in the written music but does not follow the tempo of the rest, it will produce a cacophony, not a symphony. Similarly the speed of some particular reactions does produce a deleterious effect on the human mind. The intelligence is the top performance.

Now the problem is, how can we detect this discordant musician in the genetic make up? My guess is that there are not many musicians who are dangerous if they play too fast on chromosome 21. There are possibly thou sands of genes on chromosome 21. If each of them was having a damaging effect the baby would not survive at all. The baby would not even develop. Usually, some of those genes are not sensitive to genetic dosage, and only a few of them are really capable of doing damage. How could we detect a small number of culprits amongst so many innocents? That is a very difficult detective story that we are just beginning to unravel. In fact this detective work could be avoided if we knew how to silence a whole chromosome.

The doctor treating a Down's Syndrome baby can be compared to a mechanic who receives a four cylinder engine with five spark plugs from the factory. The motor will not run normally. If the car dealer is very dull he will say this motor is no good, it is junk, and will throw it away. This is, in fact, the position of the abortionist. However, if he was an intelligent car mechanic he would open the motor, see the extra plug and disconnect it. The extra spark plug would still be there, but, if it is disconnected, the motor would run properly.

Now the pity is that we are not yet as knowledgeable as a good car mechanic. I have to tell you that bluntly. But nature is very shrewd. Nature knows the trick of how to silence a whole chromosome. For example, you know that mankind is split roughly into two halves. The most charming half of it is enjoying two X chromosomes. The other half is having only one X chromosome and a tiny little Y. B u t nature has taken the trouble to shut of f one of the two Xs in the woman. That is very good because for that reason women are not so much superior to the poor man with only one X. We have not yet fully understood how nature does that. We can see it under the microscope; however, we can see that the part of the chromosome which is silenced is not the same colour as the one which is active. If we could really understand how a target in the chromosome is suddenly affected by a special signal so that this segment of the chromosome is silenced, we could work like the intelligent car mechanic and unplug the extra 21. My impression — and this is purely an impression — is that this is not science fiction. In the future somebody, somewhere, will discover how nature does it. But at the moment nobody has an idea how to devise experiments to access that phenomenon. We cannot go forward until somebody has the intelligence to understand nature better than we do now.

We are left with the painful task of trying to unravel the genetic inheritance carried by chromosome 21. To do that there are three possible methods Two of them are well known. The third is yet to be fully established.

The first two ways are intellectually very simple. We know how to extract DNA from the cells. The DNA is one metre long in the ovum and one metre long in the sperm so that we have two metres in each cell. We can extract it, with special enzymes cut it into little pieces and begin to decode or read what is written on it. The difficulty is that there is an enormous amount of information to deal with. If we were to print one letter for each of the bases on the DNA of one human cell, the length would be roughly five or six times the total volumes of the Encyclopedia Britannica. It would be a little boring to read that, and no human mind could remember it all. But someday there will be a machine in which the whole information will be stored in the artificial memory and we will devise a system to analyse this data base, perhaps even in less than 10 years.

You have probably heard that in Paris people have said that they had unraveled the whole DNA of chromosome 21. Obviously this is not true but we hope it will happen. However, what they have done so far is to cut in pieces all the DNA extracted from chromosome 21 and attempted to define how these strings of DNA can follow each other on the chromosome. They have put milestones along the road. The analysis is not complete but the indicator system has been established along the road. What remains is to read the formula of every gene.

The second method which is already used, is to study the chromosomal abnormalities and try to analyse the few genes we can detect on chromosome 21.1 would say that there are about 20 genes which are now known in this chromosome 21. Some are known in more detail than others. Not all 20 concern us, only those which can help us to understand Down's Syndrome. The first one was discovered a long time ago by Sinet who was working with us in Paris.

The first discovery was the gene which produces super oxide dismutase. We know the gene and the whole formula of the protein is also known. What is the significance of these findings? Many people with Down's Syndrome develop a regression (when they are between 20 and 40 years of age) which resembles Alzheimer's Disease. Some say that all people with Down's Syndrome get Alzheimer's Disease. This particular diagnosis is not accurate; but it is true that a lot of people with Down's Syndrome develop a deposit of amyloid protein in the brain. We also know now that a gene which regulates this substance is on 21 and the gene which produces the substance which accumulates in the brain in Alzheimer's Disease is also on 21. It is still difficult to discover the basic mechanism of these two diseases, Alzheimer's and Down's Syndrome. The general scheme of the biochemical events required for the functioning of the brain looks like the printed circuit of a very complex computer. The research worker has to try to figure out what will happen if a particular gene is running too fast. The genes on a given chromosome are not put there at random. That this gene is at this place on our human genome is because, if it was not there, it would not be able to function harmoniously. The whole human genome is in fact an ordering of the values which work one upon the other so that the whole machinery is running smoothly and totally integrated.

Located on chromosome 21 are genes controlling the following functions: Increased production of purines, which causes a high level of uric acid in the urine of people with Down's Syndrome. Transformation of the amino acid serine combined with homocysteine to produce cystathionine. This reaction is accelerated in people with Down's Syndrome. Conversion of ATP into AMP is also accelerated in Down's Syndrome.

Transformation of adenosine to inosine by adenosine deaminese, again, is increased in people with Down's Syndrome. Serine is also essential for the production of such cholinergic substances as acetylcholine (to maintain the functioning level at the cholinergic synapses in the neural system). Three monocarbons (coming from serine) and one molecule of serine, are necessary for one molecule of acetylcholine. Therefore, in Down's Syndrome the lowered serine in the blood affects the availability and therefore the sensitivity of transmission at the cholinergic nerve endings. 20 years ago we observed that children with Down' s Syndrome who received atropine drops in their eyes showed a greater dilation of the iris and a delayed return to normal.

We now come to a discovery by Marie Peters who was studying leukaemia at the Sick Children's Hospital in Toronto at the time. Leukaemia is more frequent with Down's Syndrome children than with normal children. On examination of the hospital files, Marie Peters discovered that if normal babies and babies with the extra 21 were treated with the same amount of methotrexate, an antifolate drug for the same type or leukaemia, the drug was twice as toxic among Down's Syndrome children as among normal children. Visiting us in Paris 5 years ago, she told me about this observation. When the Toronto hospital decided to publish this discovery, I confirmed it immediately because we had taken lymphocytes of Down's Syndrome children, cultivated them in vitro and put a very heavy dose of methotrexate inside the tube. A very heavy dose killed the cells. Progressively, by changing the dose, we could demonstrate that we were killing cells which had an extra 21 with half the dose which was necessary to kill normal cells. That was the first demonstration that we could really do something in vitro and gave the impetus to a new way of looking at this very complex phenomenon. Perhaps we are not obliged to wait until we know everything to detect what is going wrong with the motor! In that sense we are playing the role of the intelligent car mechanic. In winter when your car does not start and you go to a good mechanic, he does not know anything about the law of electro chemistry at low temperature, but he knows that he should give you a new battery and your car starts.

The second breakdown concerns the thyroid metabolic chain. We know that the thyroid, is doing exactly the opposite of what the amino acid methionine does. Thyroxine will increase the input of monocarbons and block the excretion. On the contrary, methionine will block the input and increase the excretion. This has been perfectly demonstrated by people working on experimental animals who were never interested in Down's Syndrome. But we are. This was logically related to the methotrexate sensitivity discovery by Marie Peters. In Down's Syndrome there is something wrong in the metabolism of the thyroid. Even if they are very healthy and appear to have a normal thyroid equilibrium, they have a deficiency of a very complex molecule which is called reverse T3. Thyroxin is T3, which is the hormone that is lacking in mixodematous cretinism. Down's Syndrome babies have an excess of stimulation of the thyroid, i.e. they have too much TSH and as a rule, any child who has Down's Syndrome must be checked when they are young, from birth to 5 years, every six months, for thyroid function. If a dysfunction of the thyroid begins, it is very easy to compensate, but if you leave the baby with a deficiency of the thyroid for one year then they will develop mental retardation because they were using their thyroxin to compensate partly for their difficulty in monocarbon metabolism.

It is often supposed that it is the Down's Syndrome that makes such children too floppy. However, a Down's Syndrome child may have neurological syndromes which are not properly diagnosed. We have to understand that, by unraveling step by step the pathology of the mental retardation, we cannot directly cure the mental retardation, but we can surely protect the baby from an accelerated regression and severe retardation. We now know why it's that Down's Syndrome children look too floppy: because of thyroid dysfunction where reversed T3 is required to control that reaction. Possibly Down's Syndrome babies cannot make enough T3 because of the abnormal level of superoxide ions .that are destroyed.

If you look at all the amino acids, you can see that Down's Syndrome babies have abnormal equilibrium. Serine is very significantly lower in Down's Syndrome children than normal. The second amino acid that can be detected is cystine which is increased. This is highly significant. It is also significant that they urinate too much phenylalnine, methionine and methylhistidine. What does this mean? It is very simple. Remember that serine is lower as a mean in Down's Syndrome persons, cystine is higher. Serine is used to produce cystathionine which then goes on to produce cystine. This reaction runs too fast in Down's Syndrome. Most of the serine we need is made in our bodies. We use a lot of it. Adults use roughly 100 grammes per day.

It is interesting to look at the level of serine in Down's Syndrome people when they get a state resembling Alzheimer' s Disease. In that case serine becomes much lower than it was previously. What can be done? Knowing that serine is not toxic and that we manufacture a lot of it, I have bought 50 kilogrammes of serine which we give by teaspoon to babies as an adjunct to their food. We need about 1 year at least and at least 50 persons treated before we can say that there has been any improvement. At the moment we have been experimenting for 6 months but we did the first experiment long ago.

I can only give details of 4 Down's Syndrome people who have received serine. They were examined before and after they had this enriched regime. Before receiving the dose they were very low in serine; after receiving it by mouth, they were still low but higher than previously. If we give too much there seems to be no danger, it is just urinated, not accumulated in the body. The curious phenomenon is that, now, methionine is increasing in urine, and not in blood as it was previously. This is intriguing because it means that part of the serine that they have received has been transformed into methionine. It may be better to give methionine together with serine than serine alone. We are not dealing with drugs which are toxic; but the balance of amino acids input is possibly quite important. It is very difficult to see if we are now compensating properly for what was going wrong.

We can split our sample of Down's Syndrome children between those who are doing well and those who are a little psychotic and difficult. Those displaying psychotic-like behaviour possibly improve after receiving inosine and/or guanosine. One girl I treated was quite transformed in about 15 days after having received inosine; her psychotic behaviour diminished drastically. When we stopped giving inosine she started to display psychotic behaviour once again. Now this is purely pharmacological; inosine has none of the properties of a neuroleptic drug. But it has changed her behaviour.

To conclude, the situation is very complex. You have to understand that we have not found what we are looking for, which is a treatment which will entirely change the destiny of the children who are affected by Down's Syndrome.

The progress made in the last 5 years has been towards protecting them from further retardation.

The administration of folic acid is not a treatment but a kind of prevention. It does not change the motor but gives better use of the fuel. In the long run, we are not concerned about academic performance but about helping those children who are amongst the most disinherited of the children of man.

Question:

How many children do you see in a year and what percentage of those under 5 years of age have thyroid deficiency?

We see about 2000 children per year and on file we have about 8000 people. Myself, I know about 2000 of them by their first name. Nearly half of them have an excess of TSH. About half of these have normal T3 and T4: on these we do nothing. When T3 and T4 are going down we immediately give thyroxin. About 20% to 25% need thyroxin perhaps only for a year. The thyroid gets tired. To have a tired thyroid for one year is deleterious. Down's Syndrome children need a thyroid test twice a year up until they are at least 3-4 years of age.

Regarding folic acid, to the best of my knowledge, today, I would think that we should give folic acid between a half and one milligram per kilogramme per day. As far as 1 can see there is no sense in going higher as it is all passed through urine and does not seem to be useful. Folic acid helps them to have their system running a little faster so that the bad effect of the gene overdose is minimised. It is not a cure. When folic acid is used, the thyroid generally goes back to normal which shows that the thyroid is used to compensate for their deficit of monocarbons metabolism.

We treat adults with Down's Syndrome with folic acid as well and are also trying to see whether a mixed regime of serine, methionine, B12 and folic acid is helping their situation. But 2 years at least are necessary to conduct this research.

This paper was delivered by the late Professor Lejeune at a conference organised by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Order of Christian Unity and the Anna Fund held at the Medical Society of London, 3rd. November 1992.

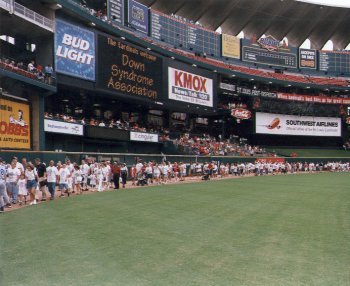

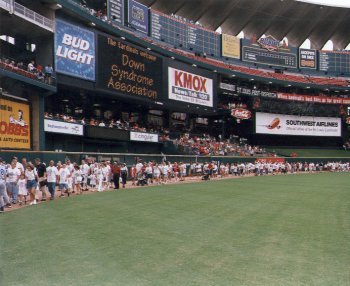

Down Syndrome Association of Greater St. Louis 2001 Buddy Walk by Dan Farrell, E-mail: dfarrell@stlcardinals.com.

The St. Louis Cardinals, Cardinals Care and the Down Syndrome Association of Greater St. Louis teamed up to host the 7th Annual Buddy Walk at Busch Stadium. This was the first time the St. Louis edition of the Buddy Walk was held at Busch Stadium, and it turned out to be great event for all.

|

|

| Credit: Cardinal's Staff Photographer. Jim Herren, Collinsville, IL |

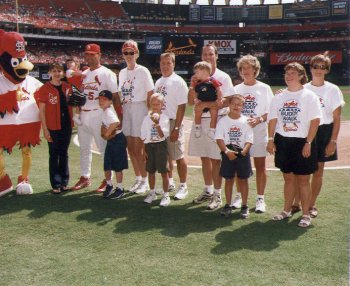

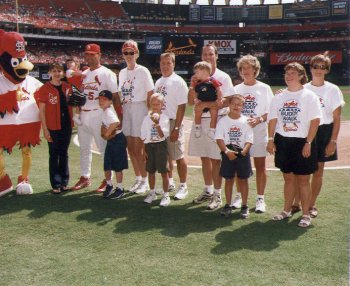

Fredbird, Diedre, Isabella & Albert Pujols, Ethan & Beth Schroeder, Tyler & Hank Schuppert, Casey & Steve Logue, Michael & Kim Nester, Lydia and Lynn Orso.

Credit: Cardinal's Staff Photographer Jim Herren, Collinsville, IL. |

The day started at 10:00 am. with a pre-game party on the Busch Stadium bus parking lot, immediately south of the stadium. The party included games, music, food, prizes, along with Fredbird and a live DJ. Close to 2,000 friends and families of DSAGSL members enjoyed the festivities, and all attendees received a uniquely designed T-shirt commemorating the event.

At the conclusion of the party, the whole crew lined up outside the stadium to take part in the first ever Buddy Walk at Busch! The walk began at 11:30 am. as Fredbird led the group for a lap around the stadium on the warning track.

As the parade circled the field, there was a great response from the fans in the stands, and some wonderful visual moments were captured on the stadium Diamond vision video board. Everyone enjoyed the walk, and there were several Busch Stadium pre-game parade firsts including many strollers, wagons, and a bicycle!

After the Walk, most of the group headed to their seats along the third baseline to enjoy the Cardinals-Dodgers game. Prior to the game, a field ceremony was conducted to introduce several families associated with DSAGSL, and three children - Ethan Schroeder, Tyler Schuppert, and Michael Nester had the honor of throwing out the ceremonial first pitch of the Game to honorary chairman for the day, Albert Pujols!

The Cardinals won the ball game, the weather was spectacular, and many families had a great day of fun and entertainment, bringing together the community of families and persons with Down syndrome.

There was also considerable media coverage of the event, helping in the goal of increasing awareness, understanding and acceptance of people with Down syndrome. Cardinals Care, the team's community foundation which supports youth initiatives in the area was responsible for funding the pre-game party along with Cardinals sponsors-Coca Cola, Ice Mountain, Hunter Hot Dogs, Nabisco, and SportService Corporation.

Pujols a Card-carrying star. 21-year-old rookie impresses with his power and his poise by Chuck Johnson. May 22, 2002, p. 2c. ©USA Today

[... He got married in November 1999 after meeting his future bride, Deidre, in a Latin dance club in Kansas City. Pujols was 18 when they met and initially fibbed about his age, telling Deidre, 3 years his senior, he was 21. He confessed on their first date, while Deidre also opened up, sharing with Pujols that she had an 8-week-old girl.

Pujols says that the moment he met Isabella, who has Down syndrome, she captured his heart.

"She is a real cutie, and when I'm not home, I miss her every day," he says. I want to be there for her and do the best I can to be a dad. I don't think of it as a responsibility. God has blessed me. He brought my wife and baby my way. I'm very thankful for that."

Pujols and his wife welcomed a new addition to the family Jan. 10 when their son, A.J. was born. [...]

Reading at an early age: Immersion key in Down syndrome by Kay Miller, E-mail: kmiller@startribune.com, Star Tribune Staff Writer. October 14, 2001. © Copyright 2001 Star Tribune. All rights reserved. Republished with permission of Star Tribune, Minneapolis-St. Paul. No further republication or redistribution is permitted without the written consent of Star Tribune.

Bret Salter wakes up asking for books.

"Book," his parents hear him call through his bedroom monitor, his cheery request becoming insistent: "Book! BOOK! BOOOOK!"

There are stacks, boxes and baskets of books in every room of Bret's home. Hand-printed labels are taped to objects at Bret-eye-level: SINK, MIRROR, PIANO, PLANT. His parents put the labels that fall off into his special wooden box.

Bret's eyes light up when he sees the box. He sits, legs akimbo, happily plunking out cards. There are 200 words in the box. Bret can read most of them.

"Walk," he reads. "Hot tea. Red couch. Spider." He stumbles slightly on the difference between "Red" and "Read" but has no trouble with "Mirror."

Bret is 2½ years old. He has Down syndrome.

Kate Bretscher-Salter was four months pregnant when she learned that she was carrying a child with Down syndrome. "I remember being so crushed at the time." But after researching the genetic disorder, two things gave her and husband Chuck Salter hope: stories of children with Down syndrome accomplishing amazing things. And the possibility of drug therapies arising from genetic research.

"I don't want to say there's a magic cure for Down syndrome," Kate said. "All I'm saying is genetics is not your destiny."

These days, young adults with Down syndrome are attending community colleges and trade schools, writing books, acting, even running for public office. Proactive parents and early immersion in literacy programs are helping such efforts.

Bret would attend college someday, his parents decided. He was 2 weeks old when they started down a determined path of intervention.

"I would much rather be criticized for having an extremely aggressive goal and shooting for that," Kate said. "If we make the assumption there's nothing we can do, we're losing half the battle."

Range of potential

It's early morning and Kate has slipped a "Love and Learning" tape into the VCR for Bret. He loves the tapes, created with companion audiotapes and books by a Michigan couple, Joe and Susan Kotlinski, for their special-needs daughter. Bret flaps his hands when the words appear.

It has taken a team of people - teachers, doctors and physical, occupational, speech and music therapists - to get Bret this far, said Kate, 41, a laboratory manager at 3M's Biomaterials Technology Center. Despite high-pressure jobs, she and Chuck, 45, a Hennepin County prosecutor who also serves as vice president of the Down Syndrome Association of Minnesota, have devoted themselves to seeking therapies that play to Bret's strengths - his love of books, bubbles and music. And his amazing memory.

At 8 a.m., Kristi Erickson, a Minneapolis Public Schools early childhood special education teacher, arrives for Bret's lesson - one of six hours of therapy he receives every week at home or at the Fraser School in Richfield.

It was Erickson who discovered that Bret was sight-reading. For months, Bret had been learning his colors from cards - with both the color and its name - taped to the stairway to the third-floor family room. Kate switched the cards around. Bret still named most of them correctly.

But when Erickson flashed a green card without the word, Bret was baffled. "Then she showed him a card with just the word GREEN and he read it!" Kate recalled.

Sight-reading at 2½ would be early for any child, but especially for children with Down syndrome, who may not speak until they are 4 or 5.

His speech therapist at Fraser was more amazed when Bret strung sentences together - "I want help," "Look in the mirror" or "I don't like that."

Is Bret unique?

"My gut says that what Bret is doing represents what is possible for a child with Down syndrome," said Dr. Margaret Horrobin, a retired HealthPartners pediatrician and co-author of "Down Syndrome: Birth to Adulthood, Giving Families an Edge," a popular text on raising children who have Down syndrome.

There's a huge range of potential among these children, Horrobin said. She and John Rynders, a retired educational psychologist at the University of Minnesota, were among the earliest advocates of language immersion for infants with Down syndrome. Decades ago, they encouraged parents to do many of the things that the Salters now do with Bret. But none of the 20 kids in their study were sight-reading at Bret's age.

"I think it's terrific what Bret is achieving, and I certainly applaud the parents for the work they're doing with him," Horrobin said. "But we have to be so careful that we don't say this is the standard - that if you're not doing it you're robbing your child of his potential.

"I don't think that most children with Down syndrome, given the same amount of stimulation, will be able to do what Bret is doing."

Opening Tupperware

"Bret isn't the only child with Down syndrome who is reading at 2," Kate said.

His progress challenges assumptions about how much a child with Down syndrome can achieve.

"It's very complicated and you can't expect them all to be the same," Kate said. "But we're learning that there's great potential even in those with very severe disabilities. It comes down to respect for a child's potential."

Because of Down syndrome, Bret has a number of genetic risk factors: He's at risk for health problems, literacy problems, problems of integrating into society, Kate said.

"You look at these and ask, 'How can we take the edge off the risk?'" she said.

Medically, the Salters learned, children with Down syndrome have physical problems that, untreated, cause developmental delays. Bret produces too little thyroid hormone, increasing his risk of cognitive delays. So they put him on thyroid medication.

"Fine motor skills are a challenge," Kate said. "A lot of that is because there's no mass on his little shoulders. If a child cannot roll over, lift his head and explore his environment, he cannot stimulate the wiring in his brain. He may sit in a corner because he can't crawl. So he can't get the sensory stimulation other kids get from pulling open the cabinet doors and picking lids off the Tupperware."

Bret's therapists have taught the Salters hundreds of techniques to help Bret acquire skills that most kids develop instinctively. Occupational therapist Sandy Daly brings in squishy toys and shows Bret how to pinch, poke and squeeze - building the "pincer" skills that he will need to button his shirt, use a pencil or turn the pages of a book. Chuck does "wheelbarrow" exercises, holding Bret by the ankles to build upper-body strength.

"Getting Bret to walk, it was like in aerobics: 'Hands down. Now put your little bottom up,'" Kate recalled. "He was OK as long as you told him what the next motion was."

Development stalled

As a baby, Bret was strong and mobile. He sat at 6 months, but by 12 months was slipping further and further behind his targets on the developmental charts. Alarmed, the Salters visited his physical-therapy class and were astonished that their normally happy son cried through class. He didn't seem to connect with his teacher.

Worse, Bret seemed detached, as if he'd given up on himself.

"We realized we had been farming out his therapy and weren't as engaged as we should be," Kate said. Bret learned best one-to-one. So the Salters negotiated with the Minneapolis schools to shift his physical therapy to their home and rescheduled all his sessions to early mornings and late afternoons so that Kate or Chuck could attend. They asked for more information. And lots of homework.

"For me, it was like a race against time," Kate said.

She read that there was a "magical" window in early childhood when all kids experience an explosion in language and learning. She also knew that neural degeneration is a hallmark of Down syndrome. How could they optimize the early years of Bret's education?

"There's always a feeling that you should be doing more," Kate said.

It was exhausting. The Salters felt overwhelmed and unsure of themselves. Sometimes they questioned why they were constantly singing, talking and reading to a baby who didn't respond. They shared their fears with other parents in a Down Syndrome Association support group whose members told them about highly verbal young adults who read, work and live independently.

"Don't give up on Bret," they said. "These kids can read. They can go to college."

The Salters decided to trust their instincts.

In February, they hired a new physical therapist and a nanny. The nanny attended Bret's therapy session and worked with him three days a week, charting his progress in a diary. That's when the big changes started. Bret began crawling and feeding himself.

This summer they hired Dawn Rode, who also works in adult group homes, to care for Bret three days a week, incorporating therapy into his daily play.

Now on a Tuesday morning Kate smiles as Bret mimics her silly songs, repeating words with perfect pitch. He twirls a musical bell toy, deliberately changing its course to create a descending scale.

Kate talks about Sujeet Desai, an 18-year-old musician with Down syndrome who plays the clarinet, violin and piano. Last spring Desai was the first special-education student in his Fayetteville, N.Y., high school to be inducted into the National Honor Society and he's been accepted at the Berkshire Hills Music Academy in South Hadley, Mass.

While the Salters believe that they are equipping Bret for something at least as exciting as what Desai has achieved, they fear that what he is now learning could be lost in his 30s or 40s, when an estimated 40 percent of people with Down syndrome develop Alzheimer's dementia.

Scientists are on the brink of creating therapeutic interventions for diseases such as Alzheimer's that have direct applicability to Down syndrome, Kate said. But that won't happen unless policymakers grasp the depth of potential that children such as Bret have.

"We're full of hope," Kate said. "We sit here at the cusp of the announcement of the Human Genome Project, where this thing called a genetic condition has the potential for becoming understandable."

Book becomes a lure

It's nearly noon. Bret has had a morning full of lessons and therapy. He should be flagging, but he's going like the Energizer Bunny.

Rode gathers the books that Bret has happily spread around him on the living room floor. She sets him on his feet and dangles a book in front of his outstretched hands.

Happily, Bret toddles toward his crib, settling down with a blanket and his beloved book.

Web Wanderings

The Magic Violin is a Christmas story for all children about hope, faith and belief.

Introduced this year, there are only 5,000 copies of this Special Limited Edition of The Magic Violin. A Christmas Gift. The gift set ($39.95 + S&H) includes a storybook, a "magic" violin and a Christmas songbook. It is a story about a girl named Emily with Down syndrome who always wanted a violin for Christmas.

But, because Emily's family thought a violin might be too hard and frustrating for her play, they never got her a violin. Then, her Aunt Mary found the magic violin. For more information, contact:

Angel Pathways

Attention: Traci Culverhouse

1432 Geddie Loop Road

Deatsville, AL 36022

(866) 846-5463

Fax: (866) 846-5468

Father's Journal

Half a Cross

Goliath lies slain in our living room, his spear also a hobby horse or an umbrella protecting Emmanuel from imaginary raindrops.

This wooden dowel across the door threshold is for upper body strength but during the 11th Station of the Cross, it becomes the transverse beam that Jesus Christ carried to Calvary, which my son places as a yoke on his shoulders.

|

|

Resolution to Allow the Recording of IEP Meetings for Students and Parents of Students with Disabilities. The petition can be found on-line at:

http://www.PetitionOnline.com/CROSS001/ or by contacting:

Edmund H. Unterreiner, III

53 Spencer Trail

St. Peters, MO 63376

(636) 936-0462

E-mail: endeavorengineering@home.com